Darkness Covered the Whole Land — Participate in Good Friday

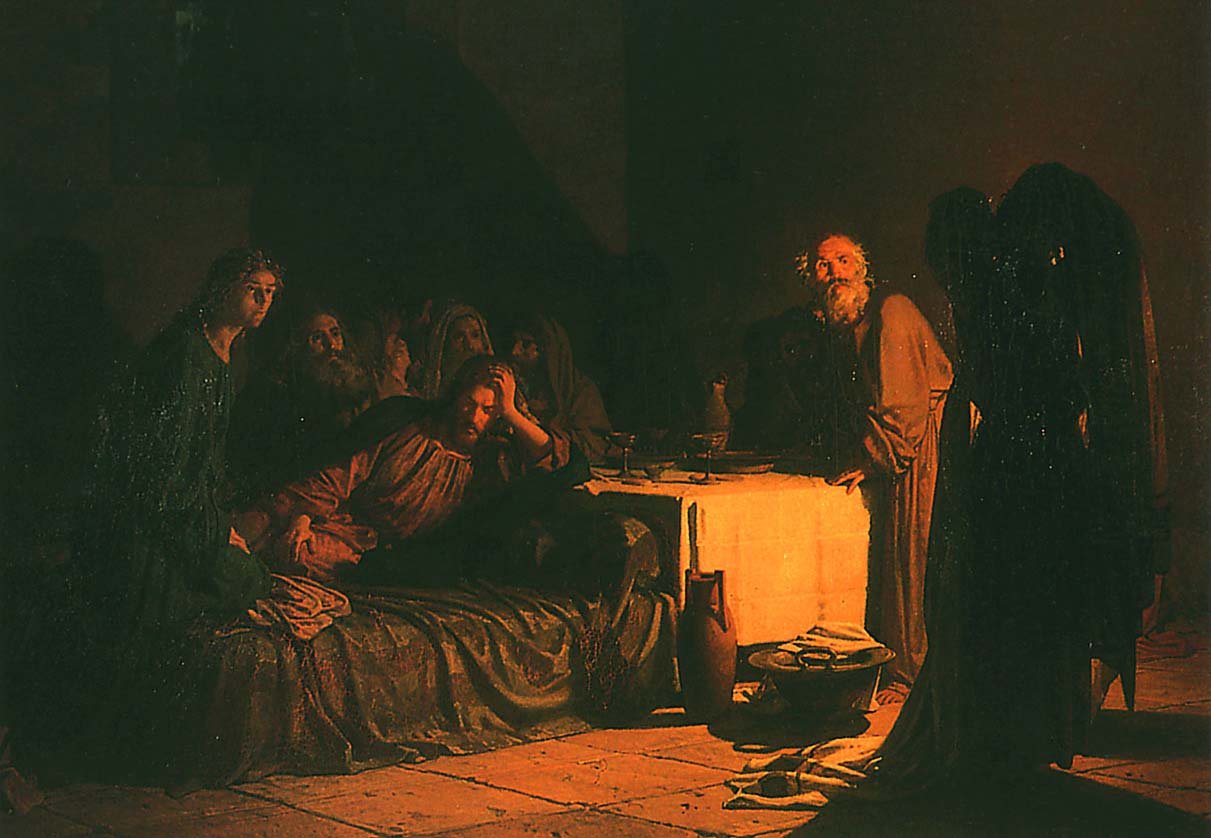

Nikolai Ge, The Last Supper

Today is Good Friday, the day we remember the passion and death of Jesus Christ. The enormity and gravity of this event is impossible for us to comprehend in any given moment of reflection. So the church has created rites and experiences of prayer, art, recitation, song, performance, sound, and—importantly—silence to give us a fuller glimpse.

Nikolai Ge was a Russian painter in the 19th century whose most famous works focused on the events surrounding the crucifixion of our Lord. Shown above, his painting of “The Last Supper” the day prior to Good Friday, known as Maundy Thursday, which celebrates the Last Supper and Jesus in the garden of Gethsamene. Here, warm light illumes the faces of Jesus and his disciples, while a shadowed Judas slinks away.

Ge pulls and hangs the fabric of Judas’s clothing. He appears feminine, quiet, and decisive. Rags from the foot washing fall over the basin of water, and the supper table is still set. Every disciple’s face is fixed on the back of Judas, only Jesus’s and Judas’s gazes turn away. Ge connects the two characters, each looking into darkness.

Ge made another painting of Judas, this time depicting a scene some hours later. Torches light the way of soldiers as they depart with Jesus in the background. As in the first painting, Ge separates and connects Judas and Jesus with shadow. The colder colored moonlit path points the viewer’s eye to the warm-lit crowd.

Notice Ge’s use of clothing again. Judas now wraps himself tightly, pensively. There is nothing else for him to see besides the betrayal of his friend and master. This painting is entitled, “Conscience, Judas.”

Ge made several more paintings showing scenes from Maundy Thursday and Good Friday. Here is one more, dramatizing the encounter of Jesus with the Roman governor, Pilate.

“What is truth?” Again, Ge emphasizes clothing and shadow. He gives short glimpses of faces. And as in “The Last Supper,” Jesus’s eyes avert from his subject, this time to his right.

Jesus in this painting reflects Ge’s characterizations of Judas—his unassertive posture, clothes dragging on the floor, shadowed visage. Remember that Judas is the only other person, besides Jesus and the two thieves, who dies during the Maundy Thursday and Good Friday sequence.

Uncomfortable as it is, Judas plays a role in bringing to pass Christ’s death and the grace he offers through it. And Nikolai Ge wants his viewers to inhabit, for a time, Judas’s perspective.

It is crucial that we become comfortable dwelling for a time in darkness. The contemporary church often prefers to tell the Easter story all year round, but for us, creatures of a fallen world, Easter does not shine as brightly without the contrast to darkness. In these three paintings, one feels as if the shadows are unstoppable. They cave in upon the scenes.

One of the most beautiful and sad practices of the western church is the rite of Tenebrae. “Tenebrae” is the Latin word for “darkness” used in the Vulgate translation of Luke 23:44, where “darkness came over the whole land” as Jesus breathes his last breath.

Beginning in the 800s AD, fifteen candles were lit inside the church. And fifteen prayers were sung. As each prayer is recited, a candle is extinguished. When only the candle in the center is left, it is taken down and hidden—not extinguished but lost to sight. And darkness envelopes the congregation. There is life in darkness.

One of the 20th and 21st centuries’ greatest English language Christian poets, Geoffrey Hill, wrote a collection of poems called “Tenebrae.” One moment in the initial poem, “The Pentecost Castle,” reminds me of this moment when the candles are darkened:

At dawn the Mass

burgeons from stone

a Jesse tree

of resurrection

budding with candle

flames the gold

and the white wafers

of the feast

and ghosts for lovevoid a few tears

of wax upon

forlorn alters

The Tenebrae candles are named “ghosts for love” who weep wax on the altar. Jesus is the “Jesse tree” who buds through candles, imagined as growing out of the resurrection stone.

Poetry, visual art, candles, prayers, songs—an event like Good Friday is best experienced through participation. When we participate in remembering Christ’s work for us, we at once acknowledge the limitations of our perspective and the wholeness of event both within and outside of our view of it. We “participate” (from participare, to take part in).

Allowing ourselves to be sad, to experience darkness takes courage and humility at the same time. Our society sometimes tells us that loneliness, sadness, and darkness are always undesirable. We carry around personal distraction machines to remind us that bright, digital light is always there to keep us company.

Wherever you’re at on this Good Friday, whether you’ve practiced a season of penitence or ignored the this time of repentance and prayer, create space for quietness. Believing in the resurrection means believing that the story isn’t over.